PETER BURR

Peter Burr is a New York-based film director and audio visual artist working in VR, videogames, installation, and performance. Founder of Cartune Xprez, he has collaborated with Porpentine, Mark Fingerhut, Brenna Murphy, and more. He has exhibited widely domestically and internationally, most recently at International Film Festival Rotterdam, Berkeley Art Center, and was part of New Museum's Artists' Vr app. He will be showing with Porpentine in Declaration - Institute for Contemporary Art Virginia's inaugural exhibition opening in October 2017, as well as in documenta 14 in June 2017. We met him at his studio in Greenpoint and talked about computer viruses, LED backlit keyboards, and Andrei Tarkovsky.

What have you been working on most recently?

I just finished a piece called Descent with Forma and Mark Fingerhut that was released in February. It’s an executable file that when launched, loads itself onto your computer as a 7-minute virus. It’s available to download from a demoscene website called pouët.net, and a commercial torrent site called bittorrent.com. The idea is that it plays like a straight video while allowing you to still use your computer running beneath it. During the course of the piece you may notice rats infesting your desktop, which you can fruitlessly struggle to clean up until, at the end, they all die on their own.

Does the program only run on a PC?

Yes, technically because Apple has their operating system locked down in a different way than Windows. We gave ourselves just three weeks to finish this work. Making this run on a Mac would involve a whole other development period. I’ve been an Apple user since 1985 but lately, in part due to limitations around VR, I have switched to working on a PC. This piece emerges from a larger inquiry into this different platform and what I can do now that I’m not working in such a hyper-controlled digital environment. It would have been great to release Descent on Mac but it felt totally adequate to release it only on PC.

Is the video available to view elsewhere?

You can watch it on Vimeo as a regular video, which is in a way unfortunate, because part of the idea is to let the piece penetrate - to go into your desktop and fuck with your computer.

What are the painting references in this work?

When Forma was describing the album to me I thought about Peter Bruegel the Elder’s paintings, especially his dense crowd scenes. So there is an effort here to integrate a medieval landscape with a crowd simulation system which ends up feeling like something from the world of Bruegel or even Hieronymus Bosch - gnarly and crowded. That was the starting point. Nothing actually got developed until the current American presidency though. That was when the ideas behind the black plague became relevant to me. A lot of social and religious upheaval that happened in those times can be connected to the way half of Europe died off and an emergent confusion consequently came to power. It felt relevant to make a plague video this past year.

Tell us about the piece that you showed at the International Film Festival Rotterdam.

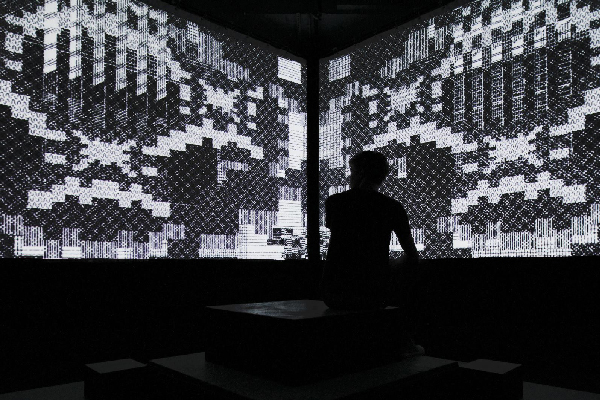

Pattern Language is a film that is meant to be seen in a dark cinema, aiming to induce a bodily oriented hallucination. This project comes from working with John Also Bennett, Porpentine, Mark Fingerhut and Brenna Murphy. I was thinking of psychoacoustic illusions and found a reference point in some of Maryanne Amacher’s compositions. She has worked on projects where she would activate specific pieces of architecture and would install speakers all over the place. She was enlivening the building by figuring out the volume of the space, creating resonant chambers so the music would shift from spot to spot and sometimes sounded like it was emanating from between your ears and not outside them.

What is Pattern Language?

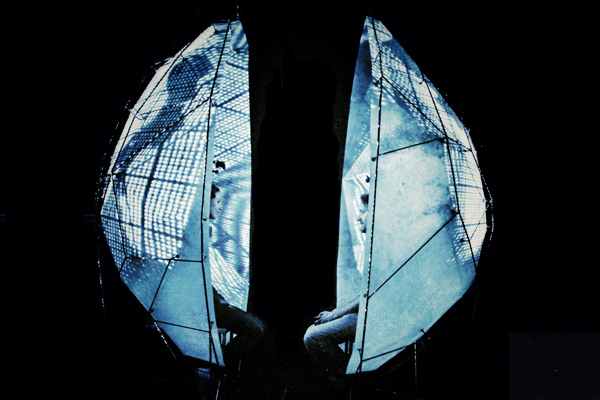

I understand it as a single piece that has dual forms. There is a site-specific four-channel version of it that requires a custom build-out and then a single channel version that is open to be screened in cinemas all over the place. The cinema version has a temporal arc in it and consequently begins and ends like any good movie. As an installation you are meant to spend an undefined amount of time in there and allow yourself to get hypnotized while it endlessly cycles, morphs and mutates.

What is the design pattern throughout the film?

One section of the piece features “The Game of Life” - a cellular automata algorithm developed in 1970 by mathematician John Conway. It’s an algorithm that dictates behavior for black and white pixels, creating very complicated logical systems.

You also installed it as an immersive installation?

Yes, first at 3LD in New York - an institution that really supports my work. In September of 2016 I did a two-month residency there. I built the space out, working with a professional sound engineer. We made a custom seating platform and built a multi-channel speaker system that was fine-tuned to the space. One of the challenges in making site-specific audiovisual works is that it’s hard to translate to home entertainment or cinema. It’s such an alien frequency.

Do you find a similar challenge in presentation of your other works?

I’m actually struggling with that lately. 3LD had really great equipment like 20,000 lumen projectors. I’m finding myself getting a bit trapped - being offered shows and not being able to get a projector that is bright enough. I’m slightly pickier about the tech than I used to be, but I don’t want to turn down shows that can’t afford a $50,000 projector either.

How did you start collaborating with Porpentine?

Porpentine is an Oakland-based game designer and writer. I got a grant from NYFA in 2015 and I pitched the idea of making a VR game-like installation at the Images Festival in Toronto. I was thinking about video games as a departure from strictly cinematic works. I came upon one of Porpentine’s video games and was very excited about the ways our work overlapped, so I used the NYFA money to hire her to be a part of this team developing the installation.

We recently decided to formalize the collaboration a bit more and are going to have our first museum show in October, the inaugural exhibition at the ICA in Richmond, Virginia. We are going to make a new series of work and the installation will premiere there.

Have you done other video games?

I come from the background of animation, installation, performance, and expanded cinema. It’s an art form that relates to video games in an oblique way. I feel like the most interesting animations right now are happening in video games and so it has become difficult to rationalize staying in this niche context of cinema, film festivals, galleries, etc., while gleaning such inspiration from games. Making a video game has offered me a great chance to look into what’s happening right now in this culture, thinking about my social context and the politics of controlling a body (on-screen and off).

Do you consider the blurred boundaries between art and commerce?

Yes, I do work across many platforms. I recently finished a commission for giphy.com - a grid of 20 looping squares that make up a dense little labyrinth. I’ve been thinking about architecture a lot in the specter of the video game I’m making with Porpentine. In our game you will control a character whose job it is to clean up an abandoned dirtscraper and reflect on the details, the subtleties of the space. This commission gave me a great opportunity to more deeply think about a philosophy that would forge such an architectural folly as the one found in our game.

What’s your architectural inspiration?

One rich source is a book called "Arcology - The City in the Image of Man" by Paolo Soleri that was published in the late 60s. I recently went to the Arizona desert where Soleri partially constructed one of these arcologies, which has remained only 4% complete for the past 20 years. He was an artist who enjoyed the metaphor of the building as a living body - the building is the silicate and we are the soft stuff inside it. It made me think about labyrinths and what a contemporary labyrinth might be.

What was the recent piece you did for New Museum’s commissioned Artists VR app?

It is a 5-minute piece that intends to make you feel dizzy and lost. This piece takes its namesake from Soleri’s concept of the arcology and envisions a version of this structure without any more life in it… just you and your avatar self.

Are you still performing?

Since 2006 I have run a video label called Cartune Xprez and have travelled the world with it presenting shows in galleries, museums, punk houses, etc which offers a great platform to perform with radical moving image work. Life shifted really drastically a few years ago for me, though, and lately I’m making work from a different wellspring - something more tethered to my insides. Originally, these Cartune Xprez performances were book-endings to events where I would curate selections of experimental animations by other artists and contextualize them through my performances - and so I was always thinking about other people’s work and thinking about my own work in a larger cultural frame. I don’t know what a performance would look like now but I am doing something for documenta 14 in June and still exploring how IRL bodies relate to motion pictures.

What happened to Cartune Xprez?

When I moved to New York I started to wonder what it would be like as a commissioning project. I came up with this concept for a show where other artists’ works could be more deeply embedded in it due to a process of all reflecting on the same touchstone. So I conceptualized a show about Andrei Tarkovsky’s film Stalker, which is one of the most powerful works of films I’ve ever seen. The source text is from Strugatsky Brother’s book "Roadside Picnic." Both are great representations of their form, pulp sci-fi novel vs. art film. I commissioned 20 interruptions and called them “commercial breaks” – taking the book and film as a starting point and then remixing them.

What was the idea behind the Stalker project?

It’s called Special Effect, short attention span Tarkovsky in an experimental animation universe. The summer that I made this I went to the Borscht Belt of abandoned resorts in upstate New York and collected lots of material. The project became a way of reinterpreting the natural life cycles inside lost man-made environments, which in Stalker is an abandoned industrial site, and thinking about a distinctly American version of that. Special Effect puts you in this world where these characters are actively searching for something inside themselves in that lost landscape.

Do you only work in black and white?

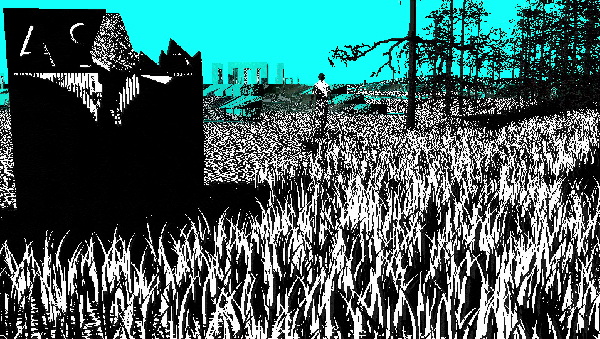

Haha, no… I don’t discriminate. When I moved to New York in 2010 I experimented with stopping my art practice and took a job making interactive children’s cartoons. Moving from Portland to New York was a funny downgrade because I had four studios in my house in Portland and my space was reduced to a small desktop in New York. It became difficult to make these celebratory rainbow works reveling in abject pop culture. Eventually I got an emulator for the first computer I ever made drawings on, which was a black and white Mac circa 1992. I began figuring out how to reinterpret this system (MacPaint) to more contemporary tools and enjoyed how the images didn’t have color; they have black and white infinite field swatches. From this, I started amassing a collection of digital halftones and patterns and turning the consequent drawings into lenticular prints and GIF loops.

I was thinking about the aesthetic of maximalism and rainbow pop culture; thinking about the sensibility of density but with a different intention than my previous work. One of the nice things about Cartune Xprez was being forced to present the work IRL as an individual in front of a crowd. I thought a lot about external context, confronting audiences, and realizing that there was something quite alienating about being overtly emo and absorbed in my own feelings. For a long time all of my work has been emanating from a catharsis, from a personal space, and I was struggling with how to make work about a larger external world rather than making something fully dominated by how I feel. It has compelled me to ground myself more in shared touchstones.